Exhibit reveals harsh truth of Cuba life

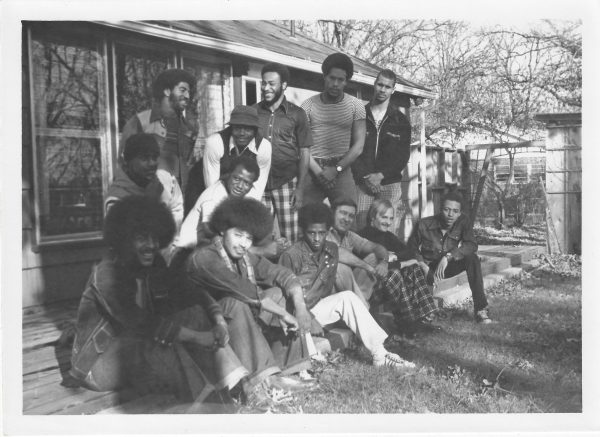

The Cuban photo exhibit, “City on the Edge of Forever,” examines the realities of everyday life.

Exotic locals and elaborate hotels are common sights for tourists in Cuba, but a stark contrast is also present.

Both the beauty and the poverty of Cuba can be seen at the photography exhibit in the Spiva Art Gallery until Sept. 19.

The showing, a collection of photos taken in Cuba the past seven years, marked the start of the Cuba Semester. The exhibit features Mary Crabb’s City on the Edge of Forever, Havana 1998 collection.

Contributed were 63 photos by faculty and students from Missouri Southern; Crabb, an anthropology professor from the University of Oklahoma; John Sleezer, a photographer from the Kansas City Star; and Dr. John Couper from Pittsburg State University.

This type of showing is something David Locher, associate professor of sociology and contributor to the exhibit, thinks is important to any international semester.

“It’s good to give some sort of idea of what the place is like visually,” he said. “People are very visual, and so seeing photographs, I think, works better than hearing descriptions or reading about a place.”

People are always interested in photography exhibits, according to Dr. Chad Stebbins, director of the Institute of International Studies. He said while other showings may include pieces too abstract for some, most photos have an appeal to all. Still, everybody will have his or her own preference.

“For me, it’s interesting to compare the black and white photos with the color ones,” Stebbins said. “You look at the black and white photos and they’re quite striking, and then some of the color photos, too, are fabulous with their use of shadows and light.”

Having so many photographers participating gives viewers a range of perspectives to see Cuba from, Locher said.

“I think if you really wanted to, you could spend a long time in Cuba taking photographs only of what you wanted to see,” Locher said.

One could also take pictures of people living in abject poverty, he said.

He took two trips to Cuba, one over winter break and one over spring break. He saw buildings that had crumbled since his first visit.

Seeing the poverty in these photographs has changed some viewers’ perspectives of Cuba, Stebbins said.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘Well I wouldn’t want to live in Cuba. Look at the conditions. Look how the buildings are deteriorating. Look how crowded the buses are.’ It’s just given an appreciation for what the Cuban population is having to endure on a daily basis.”

Locher thinks that many people’s perceptions of poverty in Cuba are inaccurate.

“When you say that people are poor in Cuba, people who haven’t been to Cuba will say, ‘Well but people are poor in the United States, people are poor in Mexico,’ but what they don’t understand is that the poor people in Cuba have professional degrees and good jobs. I mean, they’re doctors and engineers and attorneys and they’re so poor that they can only afford a pair of pants.”

The photograph of a broken down, baby blue Cadillac with a man under it had a particular effect on Locher.

“For me it was a metaphor for Cuba as a whole,” Locher said. “When it was new, it was this absolute symbol of American decadence and capitalism. It was a Cadillac, a ’52 or ’53 Cadillac and in the fifty years since then it has sort of crumbled and fallen apart and then been painted over 12 times with house paint ten different colors and that sort of thing.

Now it isn’t working, and they’re trying to keep it going. I think in all seriousness that’s kind of the whole story of the Cuban people, there they’re still trying to keep things going in spite of the fact that everything is wearing out around them.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Missouri Southern State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.