Howell speaks of Russian life

Dr. Yvonne Howell speaks about Russia in Webster hall auditorium. Her topics included its land, language and people. She spoke on scientists in the Soviet Union as well. Howell is an associate professor of Russian and international studies at the University of Richmond in Virginia.

The Russia Semester has officially started with speaker Dr. Yvonne Howell, associate professor of Russian and International Studies at the University of Richmond in Virginia.

Howell first spoke to Conrad Gubera’s Introduction to International Studies class on Sept. 1. She led an informal and open discussion with students about past and current day affairs associated with Russia.

In her second speech on Sept. 1, titled “Overview of Russia: Land, Language, People,” Howell taught the audience a brief lesson on how to read the Cyrillic alphabet and a crash course in Russian culture in Webster Hall auditorium.

A factor Americans may find different from everyday life, is Russians tend to have less personal space and are afraid of wind drafts “because of the coldness.”

Due to Russia’s large land holdings, it has several cultural and ethnic differences. A question that still lingers is whether the “new Russia” will be based on ethnic and language unity.

Further in her lecture, Howell discussed the history of the country. She went from A.D. 600-900, discussing the Slavic trading people up until the current president, Vladimir Putin.

“We should keep an eye out for the new Russia,” Howell said. “Probably something amazing will happen there.”

The final lecture Howell gave was on Friday, Sept. 3 in Webster Hall auditorium.

In “How Do Good Scientists Work with Bad Regimes?” she focused on the idea that scientists in Russia led to the founding of great studies, even though, they were in a czarist or communist regime.

“Science is not done the same way everywhere,” she said. “Science and science organizations were done differently . . . [they] were organized differently.”

With rise to the communist regime and computer technology, as in the United States, people used computers for business and personal use. According to Howell, in the Soviet Union, computer technology was “strictly limited” to military operations.

She noted when Khrushchev came into office, he promised his people a new union from Stalin. A cultural and political “thaw” was to take place.

Howell said this new era was going to be focused on truth and sincerity thanks to the computer technology.

In the totalitarian model, Howell explained how the government banned scientific goals that went against the communist goal, how the government promoted certain scientists that conformed and how it executed or arrested those scientists that did not.

Even though scientists during this regime were limited, there have not been any more Nobel Prizes ever given before or after the time of Stalin.

“Stalin poured a lot of state support into science,” Howell said.

Stalin built entire cities dedicated to the field of science. Scientists were employed by the state for life. They lived a privileged and well-funded life with a solid and free education.

“Indeed, the success of Soviet science challenge the idea that democracy is vital to science,” said one Soviet socialist in Howell’s presentation.

She went onto explain the “intellectual island.” On this “island,” scientists could do what they wish – read foreign journals, attend foreign conferences. But, off of the “island,” they were to act like complete dedicated Soviets.

With recent access to Soviet journals, people have the ability to read how these scientists were engaged in politics. According to Howell, they were not victims but players, for example, to get more funding.

“It was a culture of science with its own rules,” she said.

With a few exceptions, Howell said, the state did not always pressure the scientists to adapt and fulfill its ideals; instead it was a compromise.

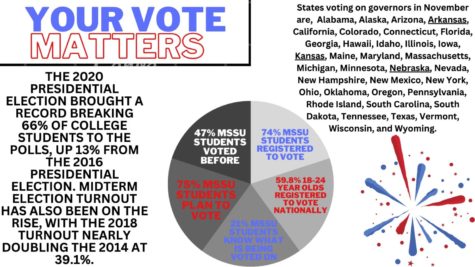

Your donation will support the student journalists of Missouri Southern State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.