Russian celebrity comes to life

Dr. John Alexander chronicles the life and work of Aleksandr Pushkin to the audience of Sept. 17. He is a professor of history, Russia and East European studies at the University of Kansas.

Not only did Aleksandr Pushkin bring life to a party, but he also brought life to poetry.

He was “mildly subversive; the master of the putdown,” said Dr. John Alexander, professor of history, Russian and East European studies from the University of Kansas in his lecture, “A Russian Celebrity: Aleksandr Pushkin.”

“He could have quite a poisonous pen,” he said.

Pushkin tried to make his living by writing, but it was difficult since there was not a big readership in Russia at the time. Even though he lived penniless for most of his life, Alexander said the poet made “every word count.”

The “short little guy [with] kinky hair [and] claw-like fingers” became a living celebrity during his lifetime from 1799-1837.

Poetry was not Pushkin’s only written work. He wrote history, fairy tails and parodies, among other things.

His first narrative poem was Ruslan and Lyudmila. This mock epic was considered a “sexy work” at its time of publish in 1820.

Pushkin’s use of word play made his poetry flow musically.

“It’s kind of a magical expression,” Alexander said. “People find [his poems] delightfully witty and fun to learn.”

His first work that “put him on the map permanently” was Eugene Onegin, which took almost nine years to complete. He was able to finish his novel while stranded at an estate by a cholera epidemic in 1830.

Being flirtatious at the parties he attended, Pushkin would play off of that by having people encourage him to write witty phrases in their albums. Pushkin, Alexander said, was great at coming up with clever and humorous lines off the top of his head.

He often boasted about his illegitimate child he had with a woman on his estate. He also brought up the fact he had African blood in him, when at the time was not heard of or talked about.

An amateur artist as well, Pushkin sketched women to whom he was attracted. He tended to draw parts of them, mostly feet.

“Supposedly, he had a foot fetish,” Alexander said.

Growing older, he became attracted to a teenager, Natalia Goncharova. He often referred to her as the “squint-eyed Madonna.” Her mother did not approve of the marriage since he had no money, drank profusely and didn’t separate his habits from his work.

In 1837, Pushkin’s brother-in-law, Baron Georges d’Antes, killed him in a duel. A foreigner and disliked by Pushkin, d’Antes was accused of pursuing Natalia; even going so far as to marrying one of Natalia’s sisters just to get closer to Natalia. Shot in the stomach, Pushkin died a few days later and was buried at a monastery.

Controversy and conspiracy theories arose from this duel. Rumors spread saying d’Antes wore armor, and the tsar had a chance to stop it. In the end, most theologians believe it happened the way most duels perspire.

Before Pushkin’s death, Tsar Nicholas I promised to look after Natalia and make sure she was taken care of.

She went into mourning then remarried and had more children. After his death, she was able to go back into the wealth of society.

By the 19th century, the Russian Imperial Academy of Arts had named part of its exhibits in Pushkin’s honor in order to preserve his legacy. There, they publish his works and research his life. Pushkin’s works have also become part of the curriculum in Russian classrooms.

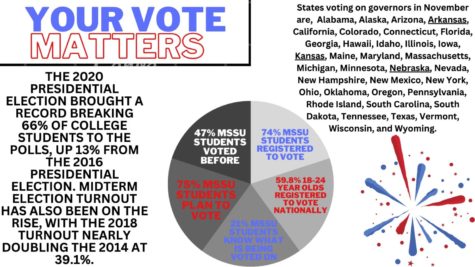

Your donation will support the student journalists of Missouri Southern State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.