People of warring nations relate opinions of war

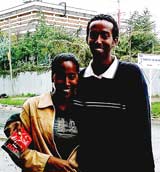

Almaz (left) and Yonas (right) are two young Eritreans in Ethiopia. Both said they long to contact their relatives in their home country, but it is illegal to do so.

In Africa, we place a great deal of emphasis on tribalism. When I am in my home country of Zambia, I identify myself as a Bemba or a Nsenga, because these are the two tribes my father and mother are from. To some people from other countries, I am simply a Zambian, and to others I am simply an African.

Ethiopia and Eritrea, much like other African countries, have a number of different tribal groups. It is easy to surmise someone else’s ethnic or tribal groups by physical features, the language they speak, and their accents and sometimes by clothing.

Ethiopia and Eritrea have two major tribal groups in common, the Tigray and the Afar. The border dispute is in the middle of the Tigray region, which extends from Ethiopia into Eritrea. In Ethiopia, the Tigrays make up about 32 percent of the population, and in Eritrea they make up about 40 percent.

The biggest tribal group in Eritrea, which makes up 50 percent of the population, is the Tigrinya, a group slightly different from the Tigray tribe. The biggest tribe in Ethiopia is the Amhara tribe whose region is in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Other major Tribal groups in Ethiopia include the Oromo, the Gurage, the Gambella, the Somali, the Sidamo and the Shankella.

When the conflict started in 1998, there was a great deal of fear among the Eritreans who lived in Ethiopia and the Ethiopians who lived in Eritrea. Both governments were engaging in mass deportation of the each other’s countrymen and women. I remember some Eritrean people I personally knew who were making plans to run away before the Ethiopian government got to them. Those who had relatives in Eritrea were very worried about how their relatives were being treated.

I decided to go out on the streets of Ethiopia and try to get a general idea from the people about how they felt about the border dispute. With my rudimentary Amharic, I spoke with one Amhara who is a cashier in a store, one Tigray who is a student at an accounting college, and one Gurage who owns a chain of supermarkets in Ethiopia. When I started talking to the Amhara, she said to me she felt the governments were to blame.

“Ethiopians and Eritreans lived together for many years, but the governments are the ones who are wrong, not the people; we are brothers and sisters,” she said.

When I asked her what she thought about the Boundary Commission’s decision, she seemed ambivalent about the decision.

“The only thing I care about is peace and not the land, but I think Ethiopia needs the land,” she said.

The Tigray was quick to point out he believed negotiation was the only way the border dispute would be solved. He told me about his many Eritrean friends who were deported and how he was unsure if he would ever see them again. He manifested a sense of hopefulness because of the international community, notably the United Nations, but he did not share the same sentiment for the African Union.

“It (the African Union) has the power to bring change, but they are useless because they don’t use their power,” he said.

I continued talking to Ethiopians and encountered some who were bitter about the war and some who did not have an opinion.

One of the people I talked to introduced me to two Eritreans. I was quite shocked to run across the Eritreans because for the longest time, I had the misconception all Eritreans were deported out of Ethiopia. I spoke to a young man and a young woman. The young woman’s name is Almaz, and the man is Yonas. Almaz is an Orthodox Christian, and Yonas is a Muslim.

They live in Ethiopia alone without their family members because all of their family members were deported. They both long to contact their relatives, but it was impossible because it is basically illegal to contact anyone in Eritrea when you are in Ethiopia. There is no way to make phone calls, send faxes or even letters to Eritrea. Also, there is no direct flight between the two countries. I wondered how they had managed to stay in Ethiopia without being deported, but both refused to make say. Many of the people who were deported from either country were accused of espionage or trying to conspire against the governments.

We talked about the conflict, and it seemed as though both of them were not even sure why there was a conflict.

Yonas said he was not sure which country should have Badme, the land that is being disputed.

Almaz on the other hand, said the land should be given to Eritrea. When I asked her why she felt that way, she did not have an answer, but it was clear she was talking out of pure nationalism. They both agreed the international community should not try to solve Africa’s problems. In addition, they both said they have a low opinion of the African Union.

Yonas said he was disappointed with the United States because in his opinion they were supporting Ethiopia because it does not have the strong Arab ties that Eritrea has.

At the end of the interview, they both said that they missed home.

They had grown up in Ethiopia, but they missed being able to go home to Eritrea, especially to see their relatives. I could see the pain in their eyes.

“Maybe the International Red Cross can help those of us who might want to go home,” Yonas said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Missouri Southern State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.